*** SPOILER WARNING: The following post inevitably reveals some of the plot details of this play, and so, if such things are important to you (they needn’t be), it is possibly best not to read this post till you’ve read or seen the play for yourself.

All quoted passages are taken from the translation by Barbara Haveland and Anne-Marie Stanton-Ife, published by Penguin Classics

In 1958, the London premiere of Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof coincided with a revival of Ibsen’s 1894 play Little Eyolf, and critics were quick in comparing the two, much to the disadvantage of Williams’ play. In New Statesman, T. C. Worsley wrote about Little Eyolf:

Its subject is a marriage and it takes that marriage apart as frankly and twice as truthfully as, say, Tennessee Williams … and it is (written though it was in 1894) just as modern if not more so …

John Barber in Daily Express thought it made Tennessee Williams “look like pap for infants”, while Alan Brien in The Spectator wrote “[Little Eyolf] wipes the smile off your face and puts the fear of God into your heart before you can say Tennessee Williams”.

All this is undoubtedly most unfair on Tennessee Williams – who, after all, did not set out to compete with Ibsen in the first place – but I think I can understand the critics’ reactions. Tennessee Williams, after all, had the reputation of being shocking, of pushing the envelope of what could be expressed on stage; while Ibsen’s image (one which still, I think, persists) was that of a staid and stolid bourgeois dramatist, writing rather stuffy plays set in middle class drawing rooms. (Brecht had, rather condescendingly, said of Ibsen’s plays that they were good for his time, and for his class.) And yet here was an Ibsen play – and not even one of his better-known ones – that shocks more deeply than what was reckoned at the time to be cutting edge drama, and which, as Alan Brien put it, “puts the fear of God into your heart”.

I can certainly vouch for the effect it has in performance. I have been to two productions, both performed (as it ideally should be, I think) in a small, intimate space; and both times, even though I knew the content, I was left shaken. My wife said to me on coming out of the first of these performances that she needed a stiff drink: I have never heard her say this before or since. She declined the suggestion that she accompany me to a second performance of this play, so emotionally harrowing and draining did she find the first, and it was only my own obsession with Ibsen, coupled, I guess, with a strong streak of masochism, that persuaded me to repeat the experience. And I remember taking the train back home afterwards, thinking: “Did Ibsen really expect people to pay to spend an evening having their souls harrowed in this manner?” But I suppose that, by this stage of his artistic career, Ibsen was writing primarily for himself, and using drama, that most public of literary art forms, to express his most private of thoughts. This is not to say that he was writing autobiography: but it is to say, I think, that he was not prepared to compromise, to sweeten the pill, or to any way dilute the strength of his moral and artistic vision. Little Eyolf is a short play – much shorter than works such as, say, A Doll’s House or An Enemy of the People: but, remarkable though those earlier works were, Ibsen had now developed ways of saying much more with much less: the unyielding and almost ruthless concentration of Little Eyolf is in itself terrifying.

The play actually opens in middle class surroundings – “an elegant, lavishly appointed conservatory”, says the stage direction – with a view of the fjord through the French windows. In the second act, we are outside, in the open air, by the shores of the fjord, and the dialogue seems to return almost obsessively to the depths of the waters, in which the child Eyolf had drowned, and from which the powerful undercurrents had carried his body out into the open sea. In the third and final act, we climb upwards: we are once again in the open air, and we look down upon the fjord below. This movement from indoors to the open air, and this vertical journeying – first downwards towards the depths, and then upwards towards the peaks – reflect the emotional temperature of the various parts of the play. The bourgeois certainties that seem implied by the “elegant, lavishly appointed conservatory” seem blown away by the end of Act 1, and in the middle act, we are forced to look into the darkest depths of the human soul. But towards the end of this act, an unforgettable image develops – of water-lilies that shoot up from the unfathomed depths of the waters and bloom suddenly and unexpectedly upon the surface. This image refers to all sorts of things. It refers to thoughts and perceptions hidden deep within our unconscious, that suddenly, and without warning, manifest themselves; and it also refers, I think, to the possibility of our rising from the depths. It is this possibility – possibility, nothing more – that the play settles upon in the beautiful but deeply uncertain final act, set high above the fjord. This final act is difficult to bring off, and many have found it disappointing. Viewed superficially, it may even seem that Ibsen is copping out – that, having presented us with the profound agony of the soul, he is merely suggesting a simplistic way out for these characters. Rita Allmers speaks of running an orphanage for homeless children, and her husband, Alfred, asks to join her. It may seem facile, perhaps even sentimental. But it is dangerous to look at anything in this play merely on the surface. When, after the first performance of the play, someone had said to Ibsen that they couldn’t imagine Rita running an orphanage, Ibsen had seemed surprised, and had asked: “Do you really think she would?” Ibsen was not depicting moral redemption in the final act; but he was depicting, I think, the possibility of these people, who, for all their flaws, are not evil, recognising the emptiness within themselves, and, at least, searching for something with which to fill that emptiness. Rita says this quite explicitly:

You’ve created an empty space inside me. And this I have to try to fill with something. Something resembling love of a sort.

Something resembling love of a sort. This is one of the most haunting lines that Ibsen ever wrote. Here are people, aware of the emptiness inside them, and knowing that, to continue to live as humans, they need to fill that emptiness with human love; but also knowing that this is precisely what they cannot do. So they try to fill that space with something – something resembling love. The means to climb higher isn’t there – not yet, anyway – but the aspirations are, and, for the moment at least, that is what matters. Brecht’s play The Life of Galileo had ended with the magnificent line “We are only at the beginning!” And at the end of Little Eyolf, that is precisely where we are: only at the beginning. As with Raskolnikov at the end of Crime and Punishment, or Levin at the end of Anna Karenina, Rita and Alfred have a long and uncertain journey still to undertake.

This final scene is difficult to bring off in performance, but I know from having experienced it that it can be done, and that when it is, the effect is unlike anything I think I have experienced in the theatre. It doesn’t wipe out the terror and the pity we had experienced earlier: one still leaves the theatre somewhat traumatised. But one does not leave in utter despair either.

But, to get to this point, where Rita and Alfred come to an understanding of the emptiness of their souls, and to an understanding of their need to fill that emptiness at least with “something resembling love”, we, like the characters, have to make a long journey. And it is this journey that forms the action of the play.

It all starts innocuously enough, in a wealthy middle class household. At the start, we see Rita, seemingly delighted that her husband Alfred had arrived home unexpectedly early the previous night from some trip he had undertaken. We see also Asta, Alfred’s half-sister: she and Rita appear to be on good terms. The only fly in the ointment appears to be Rita’s and Alfred’s ten-year son, Eyolf, who, disabled, can only hobble on his crutch. But otherwise, we appear to see a close-knit, loving family.

Eyolf, naturally, would like to be able to play with the other children, but, because of his disability, he cannot. Little Eyolf wants to be a soldier, but the other boys tell him this is impossible. “How this gnaws at my heart,” says Alfred softly to Rita. This “gnawing” becomes a sort of leitmotif in the rest of the play: we hear it often. And, soon after it is first mentioned, we have the emergence of the mysterious “Rat Maid”, a woman who rids houses of rats. “Would your lordships have anything a-gnawing here in the house?” she asks.

The appearance of the Rat Maid at just this point, repeating the image of “gnawing”, warns us that we are not inhabiting the very strictly realist world Ibsen had presented in the earlier plays of this cycle. In a sense, all plays involve the use of co-incidence: for a satisfying arc of action to play itself out in some two hours on the stage, the various incidents that define the arc, the various comings and goings, have to be carefully co-ordinated, creating co-incidences that novelists writing in the same realist tradition would normally try to avoid. The skill of the dramatist often lies in camouflaging these co-incidences, so the audience doesn’t notice the breaches in the naturalistic surface. But Ibsen, in his late plays, seemed to go out of his way to point them out. So in The Master Builder, say, immediately after Solness had spoken about the younger generation toppling the older, and of how youth will come “knocking at the door”, we hear Hilde’s knocks. Dr Herdal even points this out. Similarly here. Soon after Eyolf hears about the Rat Maid from his aunt Asta, and finds himself fascinated by her; and soon after Alfred speaks of his son’s disability “gnawing” at his heart; the Rat Maid appears in person, and asks if there is anything “a-gnawing” in the house. We do not need to examine the text closely to pick up the reference.

The consequence of pointing out rather than trying to hide the breaches in surface realism is to move the play away from a strictly realist plane, and to focus our minds on matters more abstruse. The Rat Maid has come to rid the house of that which is gnawing: she may mean rats, but we know what is gnawing at Alfred’s heart. The Rat Maid then proceeds to explain how she gets rid of the gnawing rats: she walks around the house tree times, and then plays the Jew’s harp; and when the rats hear her, they come out of the cellars, and they follow her. And she leads them to the water, sets sail in her boat, and the rats, following her, drown.

THE RAT MAID: … All those creeping, crawling creatures they follow us and follow us, out into the waters of the deep. Aye because they must, you see.

EYOLF Why must they?

THE RAT MAID: Simply because they don’t want to. Because they’re so mortal afraid of the water – so they must go out into it.

EYOLF: Do they drown then?

THE RAT MAID: Every last one.

We seem very far now from the bourgeois drawing-room realism that the opening of this play may have suggested. The Rat Wife seems (like the Button Moulder in Peer Gynt) to be a figure out of folklore. Parallels with the Pied Piper of Hamelin seem, and are no doubt intended to seem, obvious. First, the Pied Piper had rid the town of rats; and then, he had rid the town of children. That which gnaws at the heart will soon be got rid of, rats or chikdren: they’ll go because they don’t want to.

So it comes as little surprise when, by the end of this first act, Eyolf really is drowned in the fjord: the Rat Maid had played her Jew’s harp, and Eyolf had followed, presumably because he didn’t want to. And, being disabled, he could not swim. He was doomed by his disability.

But before this happens, Ibsen, perhaps rather unexpectedly given the almost dreamlike scene with the Rat Maid that had preceded it, plunges us into a scene between Alfred and Rita – a scene of the most utmost and violent passion. Alfred, we learn, had returned the previous night from a trek across the mountains, and he had had some sort of experience there – the true nature of which he does not spell out. But he has returned from the trip with a new resolution. Till now, he had devoted himself to what he felt would be his life’s work – a philosophical treatise, “On Human Responsibility”. But now, he feels, he knows what his own true responsibility is: not his writing, but his son, Eyolf. From now on, he will devote his time, his entire life, to the welfare of his poor, crippled boy.

But Alfred had not thought about Rita. Indeed, despite having been married for so many years, he barely knows her. But Rita knows herself – perhaps too well:

ALFRED [softly, eyeing her steadily]: Many’s the time when I’m almost afraid of you, Rita.

RITA [ darkly]: I’m often afraid of myself. Which is exactly why you mustn’t rouse the wickedness in me.

And then, in a scene of quite shocking frankness, it all comes out: Rita cannot keep it in. She desires Alfred – physically. And he is unable to return her passion. The previous night, when he had returned unexpectedly, she had brought out the champagne: but he had not drunk from it. It hardly needs spelling out further. Alfred has either become sexually uninterested in her, or has become impotent: either way, he is unable to respond to her still flaming sexual desire.

RITA: … And there was champagne on the table.

ALFRED: I didn’t drink any.

RITA [eyeing him bitterly]: No, that’s true. [Laughing shrilly] “You had champagne, but you touched it not,” as the poet says.

Rita says openly she wants Alfred for herself, and is not prepared to share him with anyone. She sees Asta, Alfred’s half-sister, as coming between them. And she sees her own child, Eyolf, also as a barrier.

RITA: Oh, you have no idea of all that could rise up in me, if –

ALFRED: If – ?

RITA: If I felt that you no longer cared about me. No longer loved me as you used to.

ALFRED: Oh, but Rita, my dearest – the process of human change over the years – this is bound to take place in our life too. As it does in everyone else’s.

RITA: Not in me! And I won’t hear of any change in you either. I wouldn’t be able to bear it, Alfred. I want to keep you all to myself.

And those who she feels comes between them, with whom she feels she must share her husband, are Asta, and her own son Eyolf.

Alfred is shocked – even more so, when, soon afterwards, Rita refers to “a child’s evil eye”. And it is at this point the tragedy happens – the tragedy that had been so clearly foreshadowed earlier. Ibsen, highlighting the mechanics of the drama rather than attempting to camouflage them, ends the act with a hubbub from the fjord: a boy has drowned. And yes, we know who boy is: Eyolf had slipped out unnoticed, and that which had gnawed at the heart has been taken away by the Rat Maid. Little Eyolf is dead.

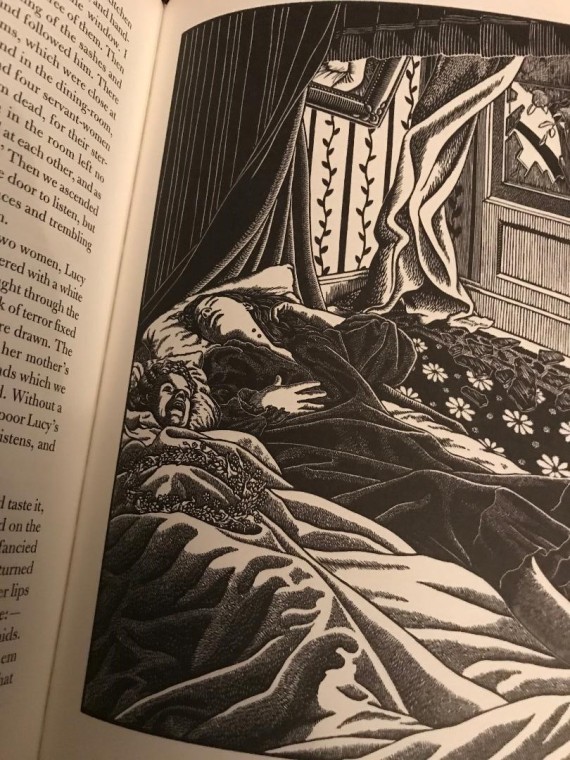

The middle act of Little Eyolf is possibly the darkest, most harrowing thing Ibsen ever wrote. We are at the bank of the fjord. Alfred and Rita haven’t spoken to each other since their child’s death, and Alfred is sitting on his own, staring out at the sea, but he knows his son’s body does not lie in the depths: there is a powerful undertow, a hidden current, that has carried Little Eyolf away. Alfred tries to make sense of what has happened, but cannot find any pattern to anything: it all seems to him entirely random, utterly pointless: reason has no part to play, for there is no reason to anything. It just happens.

Asta appears, and they find themselves reminiscing about their past together. After their father had died, they had lived together, half-brother and half-sister. It had been a hand-to-mouth existence, but it seems, in retrospect, like some prelapsarian paradise: they had been happy. They remember how Asta used to dress up in men’s clothes, and how she used to call herself Eyolf. It is clear how fond they had been of each other, and how fond they remain; it is equally clear that their feelings for each other had been more than merely that of brother and sister – indeed, in that detail of Asta dressing up as a man, there are more than hints of a certain homo-eroticism. But their relationship, as siblings, had been chaste. And for this reason, they can look back on it as, essentially, innocent.

But suddenly, Alfred pulls up short: while they had been reminiscing, he had forgotten about Little Eyolf.

ALFRED: Here I was living in memories, and he wasn’t part of them.

ASTA: Oh yes, Alfred, Little Eyolf was there behind it all.

ALFRED: He wasn’t. He slipped out of my mind. Out of my thoughts.

Alfred is horrified at himself: how could something such as this, even momentarily, slip out of his mind? And neither is this the first time this has happened. He admits to Asta that as he had been sitting there, staring out at the fjord, he had found himself wondering what they would be having for dinner that night. Alfred vaguely senses that he may not truly have loved his son, and the very possibility horrifies him.

The main section of this act is taken up with Alfred and Rita. They had been avoiding each other, but there’s no avoiding anything now. They must face the truth – about each other, about themselves. Rita tells Alfred how, when Eyolf had first fallen into the clear water, the other boys playing there had seen him lie at the bottom, his eyes open, and Alfred responds

ALFRED [rising slowly, and regarding her with quiet menace]: Were they evil, those eyes, Rita?

RITA [blanching]: Evil – !

ALFRED [going right up to her]: Were they evil eyes, staring upwards? From down there in the depths?

RITA [backing away]: Alfred – !

ALFRED [following her]: Answer me that! Were they evil child’s eyes?

RITA [ screaming] Alfred! Alfred!

Rita seems to crumble under the weight of Alfred’s accusation. She has no answer to this: her grief is compounded by her guilt. Alfred remarks bitterly that it is now as she had wished – that little Eyolf will no longer come between them. But Rita knows better: “From now on more than ever, maybe.”

But Alfred is hardly innocent himself. Rita accuses him of never really having loved Eyolf either. He used to spend all his time writing his book on “human responsibility”, of all things, and had no time for his son. He protests that he gave the book up for little Eyolf’s sake, but she knows her husband well:

RITA: Not out of love for him.

ALFRED: Why then, do you think?

RITA: Because you were consumed by self-doubt. Because you had begun to wonder whether you had any great vocation to live for in the world.

Alfred finds he cannot deny this. It is true, and Rita had noticed. But Alfred has one further accusation to fling at Rita: Eyolf’s disability, the reason Eyolf couldn’t save himself when he had fallen into the water, was Rita’s fault. When he had been a baby, they had left him sleeping soundly on the table, lying snugly among the pillows.

ALFRED: … But then you came, you, you – and lured me to you.

RITA [eyeing him defiantly]: Oh why don’t you just say you forgot the baby and everything else?

ALFRED [with suppressed fury]: Yes, that’s true. [More softly] I forgot the baby – in your arms!

RITA [shocked] Alfred! Alfred – that’s despicable of you!

Alfred accepts his part in his guilt too. So there may have been a pattern to it after all, he reflects grimly: Eyolf’s death may have been “retribution”. But this is merely posturing. As the scene progresses, the two torture each other and themselves, and they strip away from each other all the lies they had surrounded themselves with, until they face their naked unadorned souls. They had, neither of them, truly loved Eyolf: he had been a stranger to them both. Alfred asks Rita if she could leave behind all that is earthly, if she could make the leap to that other world and be united with Eyolf again, would she do so? After hesitating a while, she finds that she has no option now but to be honest with herself: no, she would not. Alfred too has to be honest with himself: he would not either. They are both creatures of this earth – this world, not any other world.

And Alfred has one final terrible truth he has to acknowledge. He had married Rita not for love of her, but for security – security for himself, and, more importantly, security for his beloved Asta. It is for her sake that he had married Rita, and had come into possession of her “green and gold forests”. Between him and Rita, there had been sexual attraction, yes, but not love, not really love.

Throughout this remarkable scene, Ibsen weaves various motifs and images, that all appear to mean far, far more than what they ostensibly signify: the powerful undercurrent that sweeps all away; the open eyes of the drowning child; the floating crutch; the insistent and implacable “gnawing” at their hearts; the green and gold forests; and, finally, the beautiful and mysterious image of the lilies that shoot up from the dark and mysterious depths of the water and bloom upon the surface. For all the harrowing nature of the content, this act is also very deeply poetic, and, in a certain sense, beautiful.

There is one further revelation before the act ends. This is something Asta had been trying to tell Alfred before, but couldn’t. However, when Alfred, convinced that he and Rita could no longer carry on living with each other, proposes to Asta that the two of them depart and live together as they used to, she has to tell him: they cannot live together as they used to: Asta has recently discovered that her birth was the consequence of an affair her mother had had, and that, hence, there is no blood tie between her and Alfred. Their past days of seeming innocence had not really been so innocent after all, and those days can no longer be recaptured.

Having reached the very bottom, there is nowhere further for Alfred and Rita to go. The last act remains for many problematic, but I find myself agreeing with translator and biographer Michael Meyer that, in this act, Ibsen achieved precisely what he had wanted.

Alfred and Rita, now frightened of being left alone together, beg Asta to stay, but she too is frightened. She had previously rejected the proposal of Borghejm, a gentle and pleasant man who is clearly besotted with her. Borghejm is an engineer, a road-builder, and, for him, life is simple: when you have obstacles in road building, you get rid of the obstacles. It’s straightforward. And so in life. Not for him the tortured doubts and mental lacerations. Now, faced with the possibility of staying on with Alfred and Rita, Asta changes her mind about Borghejm, and accepts his proposal. And she leaves behind Alfred and Rita, alone with each other, and both aware of their incapacity to love, and of the essential emptiness within themselves; and aware also of the need to fill that emptiness with something.

***

I find Little Eyolf the most terrible, and yet, in some ways, the most beautiful and poetic of Ibsen’s plays. He examines once again human lives lived on lies, on self-deceptions; he examines once again the cold emptiness within us – that “ice-church”, as he had characterised it in Brand. He takes us through the most harrowing and traumatic of journeys. When Alfred Allmers had been trekking through the mountains, he had strayed from the path, and had become lost in the wilderness. Death, he says later, seemed to him, as it were, to be a travelling companion. He had, eventually, found the path again, but his brush with death had compelled him to re-examine himself: he would now discard his precious writing, and spend all his time with Little Eyolf. But this too was yet another lie, yet another self-deception: after Little Eyolf’s death he is forced to admit that he had been motivated not by love for the child, as he had tried to persuade himself, but by doubts about his own ability. But now, with no more illusions, he has to try to understand what his experience in the mountains had really meant. And he sees within himself the same emptiness that Rita sees within herself: in this, at least, the two are united. And he, too, sees the need, as Rita puts it, of filling that emptiness with something resembling love.