I hope I’m not disappointing anyone, but this post is going to be about opera.

More specifically, about two of my personal favourite operas – Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov, and Janáček’s The Cunning Little Vixen – performances of which I had the privilege of attending over the last week.

Other than their both originating from Eastern Europe (one is Russian, the other Czech), and apart from their both being among my personal favourite works, they have little in common. Except, perhaps, that, each in its own way, they’re both quite unusual operas. Mussorgsky’s opera, based on Pushkin’s sprawling epic play, is itself a sprawling epic opera, but seems rather strangely structured: the central character Boris appears in only four of its seven scenes (in four of its nine scenes in the later 1873 version); and there are long scenes, taking up substantial parts of the opera, that seem at best only tangentially related to the central plot, making one wonder just what they are doing there. This was perhaps inevitable given that Mussorgsky (who was librettist as well as composer) had to radically cut down the text of Pushkin’s play, reducing twenty-five scenes merely to seven: this inevitably results in some narrative discontinuities, where the audience has to fill in the gaps for themselves, and also in a few threads that don’t appear to lead anywhere. It’s a work that seems to want to expand further than what can reasonably be accommodated in a single evening’s performance.

Janáček’s opera is even stranger: it is based not on a play or even a novel, but on a comic strip in a newspaper; it is virtually plotless (a summary of the incidents that occur don’t really amount to what most of us would recognise as a plot); and it tells of the interactions between humans and animals in a woodland setting. Hardly the stuff of traditional opera.

But we shouldn’t wonder at their strangeness: all works of genius are strange to some extent or other. Boris Godunov, like Mussorgsky’s later opera Khovanschina (which was left unfinished), takes us to a turbulent period of Russian history. (Although we may wonder whether there has ever been a time in Russian history that wasn’t turbulent.) The period is the late 16th century: Boris is asked by the populace to accept the crown, to prevent further civil warfare and bloodshed. He agrees, but his very first words set the tone: “My soul is heavy”. Yes, soul: this is a very Russian opera after all.

The version I saw last week performed by the Royal Opera was the earlier, and more compact, 1869 version. It is not a version I am familiar with: the recording I have (and through which I know the piece), conducted by Claudio Abbado, appears to use the longer later version from 1873, but includes also a scene from the earlier version that Mussorgsky had taken out. The differences between the 1869 and the 1879 are fascinating, but it would take a greater Mussorgsky scholar than myself to write a proper analysis of it. As for as I can see, Mussorgsky, for his later version, stripped out a brief scene in which Boris encounters the Holy Fool (who is about as archetypal a Russian figure as may be imagined); adds two long scenes involving various political and romantic machinations in Poland, where Dmitri, the Pretender, is manipulated by the Polish Princess Marina, and who is herself manipulated by the Jesuit priest Rangoni; and added also an extra scene after Boris’ death, in which we witness an attempted lynching, and where, at the end, we see the armies of the Pretender march through the land, as the Holy Fool laments the fate of the Russian people: whoever is in power, it is the people who continue to suffer. In addition to this, Mussorgsky had significantly expanded at least two other scenes. (There are most probably further changes if one were to study the scores in detail – something I am not, alas, qualified to do.)

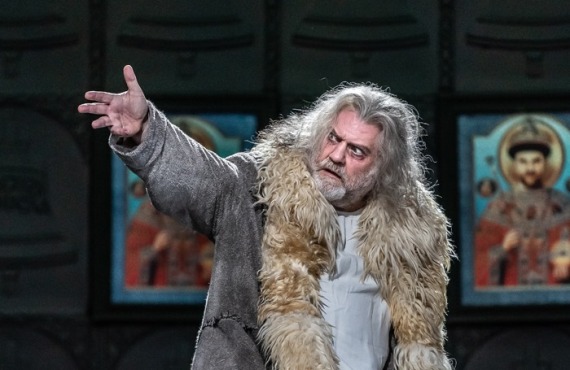

I did, I must confess, miss those extra scenes, and the extra passages Mussorgsky had composed for the later version; but even this more compact version seemed sprawling. I do not mean that as a criticism: I love the sprawl. Between the famous coronation scene at the opening, and perhaps the even more famous death scene at the end, we find ourselves in the gloom of a monastery cell, where the monk Pimen is chronicling the history of Russia (this scene is primarily expository, though not wholly so: we see also the young schismatic monk Grigory, who will later claim to be Dmitri, heir to the crown). Then, we have what seems to be a quite irrelevant scene set in a tavern, where we encounter the striking figure of the drunken monk Varlaam. True, it does relate to the main action in that we also see Grigory, now escaped from the monastery, and trying to make his way across the border into Lithuania; but the focus of this scene falls on Varlaam (sung with some gusto in this production by John Tomlinson): quite apart from anything else, he is given what must be the best “drunk” music ever composed: here was a composer who knew well what it was like to be drunk, and reproduced it unerringly in music. (In this earlier version, we do not see Varlaam again after this tavern scene: in the later version, we see him again in the final scene, attempting to lynch and hang a Catholic.)

Only after all this – some half way through the opera in its earlier version – do we encounter Boris again (after his brief appearance in the opening coronation scenes), and, perhaps to our surprise, we encounter him as a gentle and tender man, loving and solicitous of his children. But his soul is heavy: Prince Dmitri – the real prince Dmitri, not the one who later pretends to be him – had been murdered: he was a mere child. According to Pimen’s narration, it was Boris who had ordered the murder. We never quite get to know the truth of this. But in the terrifying final moments of this particular scene, we see Boris tortured with guilt, and hallucinating: he sees the murdered child appearing to him, and he cries out in terror, disclaiming his guilt. The music Mussorgsky provides for this really does make my hair stand on end: I really know nothing in any other opera to match this for sheer terror.

Some day, I’d love to see the later, more expanded version, but I can’t complain: this was every bit as majestic and as imposing and as dark and terrifying as I have always imagined this opera to be. Bryn Terfel as Boris was simply extraordinary, projecting both the tender side of the character, and also the tortured and demonic side, with equal conviction. I am not really qualified to comment on the musical aspects of the performance, but Marc Albrecht’s conducting, and the orchestra’s playing – and also, in this of all operas, the singing of the chorus: it can be argued that the people are the real protagonists here – left, as far as I was concerned, at least, absolutely nothing to be desired.

(I have now seen Bryn Terfel live on three occasions – as Hans Sachs, as Falstaff, and now, as Boris Godunov. Not a bad threesome!)

With The Cunning Little Vixen, we enter a very different world. We are no longer dealing with kings and pretenders and marching armies – we are in a forest, and the first orchestral sounds we hear seem to evoke the wind rustling the leaves, and the chirping of insects. A forester takes a nap, and a frog lands on his nose. On waking, he finds a fox cub, and takes her home to be a sort of pet for the children. The forester, and all the animals – the fox, the frog, the various birds, the mosquitoes – all sing.

The music is certainly very beautiful but at this stage, one is entitled to ask – What is Janáček playing at? The English title suggests a cute, Disneyfied view of the animal world, but the English title is misleading: the original Czech title is Příhody lišky Bystroušky, which, roughly translated, means (I’m told) “The Adventures of Vixen Sharp-ears“. Somewhat less Disneyesque than the English title perhaps, but it still doesn’t help us much. A summary of the plot, such as it is, doesn’t tell us much either: the fox cub grows up into a vixen, wards off the advances of the dog and kills all the chickens (no Disneyesque cuteness here!), runs off back into the forest, drives out the badger and takes over his home, falls in love and marries a fox (to ecstatic singing from all the other woodland animals), has many fox cubs of her own, and is then, all of a sudden and quite out of the blue, shot by a poacher. And the vixen’s death isn’t even the climactic point of the opera: the orchestra is given a few bars of sad, reflective music on the vixen’s death, and then we move on. In contrast to Boris Godunov, where death seems an earth-shattering event, here, death is presented merely as something that happens every day: it’s no big deal really.

Alongside this, we get the world of the humans: we see the forester at home with his wife; later, we see him in a tavern with a priest and a schoolmaster (Janáček’s drunk music is very different from Mussorgsky’s); the schoolmaster is pining for someone named Terynka, but his love is unrequited; while the priest, returning home tipsy, reflects on the time he had been falsely accused of a sexual misdemeanour. Later, we find that Terynka (still unseen), is to marry someone called Harašta, who is also a poacher: the schoolmaster’s love is fated to remain unrequited. The priest, meanwhile, has left: we are told briefly that he is lonely and homesick. And so on. A lot of incidents, yes, but they refuse to gel into anything resembling a coherent narrative line. Everything just seems to happen – with nothing much leading up to them, and nothing much resulting from them. Even the death of the principal character, the vixen. These things just happen – and that’s all. Even death.

To get some idea what Janáček was “playing at”, we must look to the music.

I’m truly sorry Man’s dominion

Has broken Nature’s social union…

It is “Nature’s social union” that Burns speaks of that Janáček here depicts in his music. On Saturday night, the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Simon Rattle, performed all three acts without an interval, and the whole thing emerged like a vast orchestral tone poem with voices, an all-embracing paean to nature, and to its eternal cycles of self-renewal. But of course, the fact that Nature renews herself regularly is scant consolation to us poor sods who face inevitable extinction: and this is acknowledged. The climactic point of the opera comes not with the death of the vixen, but with the Forester’s rueful monologue, in which he reflects sadly, though not bitterly, on the passage of time, and, by implication, on his own inevitable extinction. The music here is almost unbearably poignant: Simon Rattle says in his programme notes that the ending of the opera leaves him in tears, and Janáček himself had asked for this music to be played at his own funeral. I myself find it very hard to listen to this monologue without thinking of Wordsworth’s line “that there hath passed away a glory from the earth”. And yet, this is not quite the last word. Once again, the forester falls asleep, as he had done at the start of the opera, and once again, a frog jumps on to his nose, but it’s not the same frog as at the beginning: it is that’s frog’s grandchild. And in the final bars, the music itself seems to expand to fill the void with sounds of what I can only describe as ecstasy.

Lucy Crowe as the Vixen, and Gerard Finley as the forester, in “The Cunning Little Vixen”. (Picture courtesy London Symphony Orchestra)

It’s not a long opera: it’s only about 90 or so minutes – shorter than some of Wagner’s single acts. But in that 90 minutes, we find music that is, by turns, gentle, nostalgic, boisterous, exuberant, calm and nocturnal, joyous and celebratory … and even, at times, dark and tragic: the music that opens the third act, say, speaks of death as surely as does any funeral march in a Mahler symphony. This opera, for me, is Janáček’s Lied von der Erde, but how different his focus is from Mahler’s! In both works, I suppose, the sadness and the angst are, as it were, sublimated into a sort of ecstasy, but where, in Mahler, the longing fades away at the end, serenely into silence, here, we seem overwhelmed by the sheer plenitude of Life itself.

Of the performance, there is not really anything I can say other than it held me spellbound throughout. The London Symphony Orchestra produced the most extraordinary sounds and it’s hard to imagine this cast – led by Lucy Crowe as the Vixen and Gerard Finley as the forester (with a telling cameos from Hanno Muller-Brachman as the poacher Harašta, and Sophia Burgos as the Fox) – being bettered. I am not entirely sure what, if anything, Peter Sellers’ semi-staging added to the proceedings, but the way I felt on leaving the Barbican, I was in no frame of mind to complain.

Well, I suppose I’ve probably spent my entire annual opera allowance over just a few days. But it was worth it. I wouldn’t have missed these for anything.